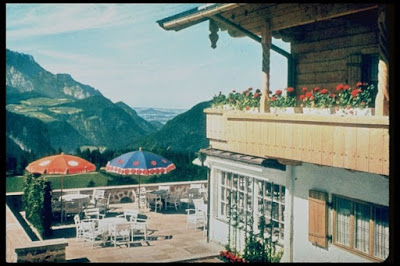

Hitlers - the Berghof home

World War II: Race to Seize Berchtesgaden

6/12/2006 • WORLD WAR II

In May 1945, as the war in Europe drew to a close, two great prizes remained. The first, Berlin, was almost completely in the hands of the Soviets. The second, Berchtesgaden, home to Adolf Hitler’s famous mountain retreat, remained to be captured.

For months, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and other Allied commanders had worried about the possible existence of a ‘national redoubt’ in Bavaria and Austria. They were concerned that thousands of Nazi diehards would take to the rugged mountains, sustain themselves with copious supplies stored up over the course of many years and fight a guerrilla-style war against the Allies. Fortunately, the redoubt existed more in the minds of German propagandists and the nightmares of Allied leaders than in the Bavarian Alps. By May most Allied officers had begun to understand this. They faced a German army with very little fight left. Hordes of prisoners clogged the autobahn. The German soldiers still resisting did so primarily against the Russians and most of the others fled westward in hopes of surrendering to the British or the Americans.

Accordingly, Berchtesgaden changed from a strategic to a prestige objective. This was the place where Hitler had planned his conquest of Europe, the place where he had hosted heads of state, the place where the German dictator had relaxed and held forth on various topics to an intimate retinue of party cronies. It was the second seat of government outside of Berlin. Every Allied unit in the area, whether French or American, desperately wanted to capture Berchtesgaden. The unit that did so would win for itself historical immortality as the conquerors of the crown jewel of Hitler’s evil empire. At least that was the thinking.

SPONSORED CONTENT

The 7th Infantry Regiment, the ‘Cottonbalers,’ had fought its way from North Africa to Germany. The unit enjoyed a proud combat heritage dating back to the War of 1812. During World War II, the regiment, operating as part of the 3rd Infantry Division, carried out four amphibious invasions, numerous river crossings and fought in such costly battles as Sicily, Anzio, southern France, the Vosges and the Colmar Pocket. Quite probably no other regiment in the U.S. Army in World War II exceeded the 7th in combat time.

The proud veteran soldiers of this tradition-rich unit were among those vying to seize Berchtesgaden. They figured it was their just dessert after so many hard years of fighting. Many of them had heard stories about the food and liquor stored at ‘Hitler’s house.’ On May 2, fresh from the capture of Munich and a tour of the infamous Dachau concentration camp, the regiment was back on the move, this time bound for Salzburg, Austria, which it took with no opposition.

National Archives

Troopers from the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment march into Berchtesgaden the day after the 7th Regiment moved through the town. Unlike the Cottonbalers, the men of the 101st stayed.

The easy capture of Salzburg surprised 3rd Infantry Division commander Maj. Gen. John W. ‘Iron Mike’ O’Daniel because he expected a tough fight, like the one his troops had experienced a couple weeks earlier at Nuremberg. In looking at a map, O’Daniel realized that the 7th Infantry was now in perfect position to make a dash for Berchtesgaden. The lure of capturing this objective was well nigh irresistible. ‘By that time the prize of Berchtesgaden was so radiant that it was obvious that considerable fame and renown would come to the unit that was first to reach Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest,’ Major William Rosson, one of O’Daniel’s staff officers said. ‘We were resolved to be the first into Berchtesgaden.’

There was only one problem with that resolution. Eisenhower and his Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) staff had already bestowed the honor upon two other units, the French 2nd Armored and the American 101st Airborne divisions. If the French got Berchtesgaden they would see it as an enormous triumph over Germany, or at the very least some kind of redress for the humiliation of their defeat in 1940. If the 101st captured the prize, Eisenhower expected that it would only add an additional laurel to a unit that was now arguably the most famous outfit in the Army after its epic stand at Bastogne. Eisenhower was doubtless aware of the 3rd’s proximity to Berchtesgaden, but given that the general and other brass expected the 3rd Division to run into a real fight in Salzburg, they probably dismissed O’Daniel’s division as a likely contender. Of course, events on the ground confused such easily formulated intentions.

Very simply, as the situation existed on the morning of May 4, the French 2nd Armored and the American 101st Airborne, the ‘Screaming Eagles,’ were not in as good a position to take Berchtesgaden as O’Daniel’s 3rd Infantry Division. His 7th Regiment controlled the only two remaining bridges over the Saalach River. One was a damaged railroad bridge outside Piding and the second a small wooden bridge nearby. Anyone wishing to get to Berchtesgaden would have to cross the Saalach over one of these bridges. On the morning of the 4th, even though his earlier request to capture Berchtesgaden had been denied by superiors, O’Daniel decided to make the attempt anyway. The tactical situation dictated this course of action but, more than that, he wanted the great prize for his division. The 3rd ‘Rock of the Marne’ Infantry Division had suffered more casualties than any other division in the U.S. Army. It had fought its way from the beaches of North Africa to the Bavarian Alps, all without a great deal of publicity. O’Daniel felt, perhaps with some justification, that his men deserved the chance.

At about 1000 hours that morning, O’Daniel visited the German-born Colonel John A. Heintges, the commander of the 7th Infantry. Heintges, a popular commander, had ordered his engineers to work feverishly through the night to strengthen the railroad bridge so that it could accommodate the 7th Infantry’s vehicles.

O’Daniel and Heintges spoke alone. Although there had been a small snowstorm a couple days before leaving a few inches of snow on the ground, this day was warm and clear. O’Daniel turned to Heintges, ‘Do you think you can go into Berchtesgaden?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Heintges responded. ‘I have a plan all made for it, and all you have to do is give me the word and we’re on our way.’

O’Daniel asked him if the railroad bridge was ready. Heintges nodded. ‘I did not get permission to go into Berchtesgaden,’ O’Daniel told him. ‘Do you think you can do it?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, go.’

Heintges did not waste a second. He immediately spoke with his 1st and 3rd battalion commanders and told them to move out.

The troops, along with their armored and artillery support, crossed the bridge and fanned out. The 1st Battalion, led by the regimental ‘Battle Patrol,’ a special reconnaissance formation under the command of Lieutenant William Miller, headed west on the most direct route, through Bad Reichenhall, while the 3rd Battalion swung east on the autobahn. The two pincers were supposed to proceed deliberately, not recklessly, and meet in Berchtesgaden. In the meantime, O’Daniel set up a roadblock and plenty of guards at the valuable bridge his men had just crossed. He left orders that no one was to cross without his express orders and immediately set about making himself difficult to contact.

After cruising through Bad Reichenhall, Miller’s Battle Patrol and the 1st Battalion ran into some resistance at a mountain pass. Some SS troops were defending the pass, a natural defile that could have held up the battalion indefinitely. The Cottonbalers simply backed up, set up their artillery and fired away at the SS, who melted back into the mountains. From there the Americans hit a few roadblocks and mines but nothing really serious.

In the east, L Company led the 3rd Battalion down the autobahn. The commander of L Company, Lieutenant Sherman Pratt, had risen from the ranks to become an officer. Bright, articulate, upbeat and blessed with great resolve, he had found opportunity in the Army as an escape from economic privation and family problems. He had joined the 7th in 1939 and immediately took to military life.

By the time the regiment entered combat in North Africa in November 1942, Pratt had risen to sergeant. For the next 212 years he served with the 7th Infantry in various NCO jobs. At Anzio he was severely wounded by German artillery, but he managed to return in time for the breakout and liberation of Rome. Eventually his superb battlefield leadership led to an opportunity for a commission, and he took it. He quickly rose from platoon leader to command of L Company. Pratt was the very embodiment of those 7th Infantry veterans who had fought their way across two continents, in the process suffering tremendous adversity. He and so many other survivors wanted Berchtesgaden as a reward for overcoming that adversity.

National Archives

Troopers of the 3rd Division question recently surrendered German troops on the road to Berchtesgaden. As they advanced, the ‘Cottonbalers’ from the 7th Regiment moved cautiously, suspecting a German ambush along the road to Hitler’s retreat. Fortunately for them, resistance was almost nonexistent.

Now, as morning turned to afternoon on the 4th, Pratt and his company rolled cautiously down the autobahn. ‘After an hour or so we had covered almost 10 miles, or approximately half the distance to the objective,’ Pratt reported. ‘The going, however, was weird and scary. I was most apprehensive. The hills on both sides of the gorge were steep, and we were confined in a very narrow and restricted area.’ In other words, the terrain was ideal for an ambush and, for all Pratt knew, plenty of SS troops waited around the next bend. The only excitement came when an American tank opened up on a German armored car and blew it up. The column proceeded unmolested all the way to Berchtesgaden, arriving there at 1600. ‘Berchtesgaden looked like a village from a fairy tale,’ Pratt said. ‘Its houses were of Alpine architecture and design. Some had gingerbread decorations.’

Pratt’s group got to Berchtesgaden shortly after a platoon from the 7th Regiment’s Battle Patrol entered the town at the head of the 1st Battalion at 1558. There were some German soldiers in the town, but they were in no mood to fight. Isadore Valenti, a medic with K Company, wrote, ‘.50-caliber machine-gun carrying jeeps and half tracks took up positions inside the square, bagging the entire enemy force in one quick move.’ Valenti and the other Cottonbalers captured 2,000 enemy soldiers. ‘The streets were lined with German officers and a few noncommissioned officers and other ranks as well,’ Major Rosson recalled. ‘The officers were in their gray long coats, with side arms and baggage, awaiting orders.’ Among the prisoners was Hermann Göring’s nephew Fritz. The younger Göring presented himself to Heintges, who had come into town with the 1st Battalion. ‘He surrendered to me in a typical military fashion,’ Heintges remembered. ‘He took off his belt with pistol and dagger and handed it to me in a little ceremony in the square right in the middle of Berchtesgaden.’ After the surrender Göring and Heintges went into a local Gasthaus and split a bottle of wine. Heintges then asked Göring why he remained in the town. ‘He said that he had been left behind to turn over his uncle Hermann Goring’s administrative headquarters and all the records,’ Heintges remembered. The Cottonbalers found the headquarters to be a complex of one-story buildings. Inside were the records for the Luftwaffe.

As soldiers of the 1st and 3rd battalions began exploring the town, Lieutenant Pratt took one of his platoons and some tanks on a mission to ‘liberate’ Hitler’s home on Kehlstein Mountain a few miles outside of town. A complex that included an SS barracks and the homes of other high-ranking Nazi leaders surrounded the Führer‘s house. ‘We were winding our way up the steep and winding mountain road,’ Pratt recalled. ‘The air was clear and crisp with almost unlimited visibility. We rounded a bend and there before us in a broad opening lay the ruins of what had once been Hitler’s house and the SS barracks.’ The Royal Air Force had bombed much of the complex on April 25. Pratt and other 7th infantrymen dismounted and began poking around the buildings. ‘Everyone in my group was struck into silence…by the significance of the time and place. After all the years of struggle and destruction, the killing, pain and suffering…here, for sure, was the end of it.’ Pratt and his men engaged in some minor looting and then went back into Berchtesgaden. A few other Cottonbalers inspected the elevator shaft that led to the teahouse atop Kehlstein Mountain.

At the same time, Valenti, the veteran medic who had seen a great deal of tragedy and heartbreak over the past two years, also explored Hitler’s house and some of the buildings around it. ‘We couldn’t believe what we saw. The walls were covered with shelves and the shelves were stocked with all kinds of wines, champagnes and liqueurs. The food bins were well stocked with a variety of canned hams, cheese and two-gallon cans containing pickles.’ Valenti and his friends sat in Hitler’s great room, where he had once entertained heads of state, and drank his wine. Before the war, Valenti, the son of Italian immigrants, had been a coal miner. He never dreamed he would get to see something like this. He persuaded a buddy to take a picture of him lounging on the hillside next to Hitler’s house.

National Archives

Soldiers of O’Daniel’s hard-fighting division enjoy the fruits of their labors by toasting with wine taken in the Nazi complex at Berchtesgaden. Sixty years later, the tales of the parties thrown in and around the Nazi complex on V-E Day are legendary and offer a fitting conclusion to the story of the Allied campaign to liberate Europe.

Most of the Cottonbalers did not visit the Berghof, as the home was known. They were down in Berchtesgaden hunting for other treasures. Heintges, who had set up his command post in a small hotel, watched in great amusement as his men availed themselves of a nearby warehouse full of cheese. ‘Our soldiers were rolling these big cheese wheels down the streets. I don’t know how many dozens of these cheeses we found and rolled out.’ The troops found plenty of shelter along with various bottles of liquor, more food and a couple of Göring’s special automobiles, one of which was bulletproof and could fit 14 people. The soldiers also found Lt. Gen. Gustav Kastner-Kirkdorf, a member of Hitler’s staff, dead in his bed. He had committed suicide with a Luger pistol, and his brains were all over his plush pillow. A Cottonbaler officer promptly liberated the Luger. Some of Heintges’ other officers brought him a Nazi flag that had flown over Hitler’s house. The colonel ordered that it be cut into pieces and passed out among his officers. Later that evening he was sampling some of the local food when his S-4 reported a major find: In a storage vault underneath a villa, soldiers had discovered Hermann Göring’s personal liquor stock. The stash, remembered Heintges, consisted of ‘16,000 bottles of all kinds of liquor. We had Cordon Rouge, Cordon Bleu Champagne…and we had Johnny Walker’s Red Label, Black Label, American whiskeys. You name it, we had it. Hermann Göring was well supplied.’ Knowing that other units would soon descend on Berchtesgaden, Heintges quietly arranged for six of his trucks to haul much of the liquor to Salzburg, where his 2nd Battalion could safely hide it. This was the largest single trophy the Cottonbalers collected from Berchtesgaden. Most of the humble foot soldiers would leave the area with only small items that could be easily carried.

National Archives

Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Wallace (right) speaks with the mayor of Berchtesgaden and local dignitaries after entering the town on May 4.

Throughout May 4, as the 7th Infantry moved into Berchtesgaden and established control of the area, O’Daniel made sure that the bridges over the Saalach remained closed to the French and the 101st. At approximately 1700, French General Jacques Philippe Leclerc attempted to cross the railroad bridge with his division and head for Berchtesgaden. Cottonbalers would not let him cross. ‘He was standing upright in his vehicle assuming the role of commander with authority and great assertiveness,’ Major Rosson said. Another Cottonbaler officer, Lt. Col. Lloyd Ramsey, told the French general that he had orders to let no one cross. Fuming, Leclerc demanded to speak to O’Daniel. After trying to give him the runaround, Ramsey and the officers agreed to Leclerc’s request. The two generals argued for a time. Leclrec demanded that he be allowed to pass; O’Daniel just as stridently refused. Only when O’Daniel received word that Heintges had, in fact, reached Berchtesgaden, did he allow the French and the 101st to pass. Earlier the Screaming Eagles had succeeded in finding a small footbridge and sending some patrols across, but they were nowhere near Berchtesgaden and, if they wanted to cross in real strength, they needed O’Daniel’s bridges. Countrymen or not, O’Daniel would not let them pass until the race was over and his men had won the prize. The French and Screaming Eagles were mixed up in a traffic jam near the railway bridge at the Saalach. Not until later in the evening of May 4, approximately 2000, did the first French troops reach Berchtesgaden. The paratroopers got there the following morning, probably sometime between 0900 and 1000.

In the early morning hours of May 5, a polite French staff officer visited Heintges and worked out the occupation zones in the area. ‘I took the railroad track which ran right through the middle of Berchtesgaden,’ Heintges remembered. He gave the French everything else, including Hitler’s home and its environs. ‘This was a terrific psychological thing for the French,’ he said. ‘So, I gave it to them because I knew that it would be a good thing for international politics.’

In so doing, Heintges unwittingly sowed the seeds for trouble. Several hours later, well after sunrise, Heintges decided that he and his soldiers should hop aboard trucks and jeeps, go back up to the ruins of Hitler’s house and raise the American flag. By that time, French soldiers had blocked off the approaches to the complex. This was their occupation zone, and they obviously thought of themselves as its conquerors. Most likely, the French soldiers had no idea that the 7th had taken the place first. By allowing the French to set up their occupation zone here, Heintges had directly created this problem. When he and his men attempted to drive into the complex, the French halted them. ‘I’m the…commander of the regiment that captured this place,’ Heintges said. ‘We’re just going up there with our troops to look over the place and raise our flag.’

National Archives

Staff Sergeant Bennett Walters (left) and Pfc Nick Urick raise the Stars and Stripes over Berchtesgaden during a hastily convened flag-raising ceremony on May 5. The event was marred by controversy when French troops in town initially refused permission for the Americans to perform the flag raising.

The French refused to let them pass. An ugly argument ensued. There was hollering, and even some pushing and shoving. Colonel Heintges defused the situation by speaking to several French officers and agreeing that there would be a joint flag-raising ceremony. When the moment came, however, the French flag brought to the ceremony was so big that it dragged on the ground, and in the end it was only Old Glory that flew over the hastily assembled troops. Heintges, his battalion commanders and several of his platoons, including one from Lieutenant Pratt’s L Company, lined up, stood at attention and saluted as the flag was raised in the light of a sunny spring sky. At the request of his battalion CO, Pratt had chosen one of his best men, Staff Sgt. Bennett Walters, to represent the 3rd Battalion in raising the flag. Private First Class Nick Urick of A Company represented the 1st Battalion. The flag raising took only a minute or two. Several war correspondents snapped photographs, and that was that. The Cottonbalers got back on their trucks and returned to Berchtesgaden, never to return to the Berghof, the complex they had conquered. They left behind no billboards or signs to mark their feat nor any indicator that the 7th Infantry had been the first ones there. Heintges should have made sure this was done. By not doing so, he left open the possibility that other Allied soldiers would believe themselves to be the conquerors of the Berghof.

Heintges returned to his command post and was soon visited by Colonel Robert Sink, the commander of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The two men were old friends, and they warmly greeted each other. They then sat down for a nice lunch and went up to Heintges’ room for a few drinks.

Sink turned to Heintges and said: ‘Well, Johnny, I’m up here…to relieve you. My regiment is on the way up here.’

Heintges was surprised because the 3rd Division staff had led him to believe that the 7th Infantry would get to stay in Berchtesgaden for a while. ‘I just talked to division a little while ago,’ Heintges uttered, ‘and they told me I’d be up here for five or six days.’

‘Oh yes,’ Sink replied, ‘but those plans were all changed and you’re going back to Salzburg.’

Heintges excused himself, called the 3rd Division and found out that Sink was correct. The 7th Infantry had orders to return to Salzburg, its original — and authorized — zone of operations. The Cottonbalers spent one more night in Berchtesgaden and cleared out the next day, May 6. As they did so, Colonel Heintges and Lt. Col. Ramsey stood next to their jeeps in the middle of town. They watched the last trucks of the 7th Infantry leave Berchtesgaden and enjoyed one last, wistful gaze at their great trophy. Heintges acknowledged to Ramsey: ‘Boy, this is a hell of a note. Here we captured the last prize of the war, and we haven’t got a damn thing to show for it.’ His words were very prophetic.

By this time, Berchtesgaden and the Berghof were alive with Allied soldiers, especially paratroopers from the 101st, many of whom believed they had gotten there first. The Cottonbalers had left behind little evidence of their presence. Perhaps they were too war weary to care. Their looting, as a result of strict orders from Heintges, was limited, and somehow they did not encounter the paratroopers in the town or at the Berghof. In the confusion, many of the paratroopers, including several members of E Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, naturally thought that they had been the first ones into Berchtesgaden.

Thus, as the war ended and the 101st Airborne Division occupied Berchtesgaden and its environs, the mistaken notion that they had bagged this great prize took hold. Thousands of tourists from the Allied armies visited Berchtesgaden that summer. Since the paratroopers were there, most of the visitors assumed that they had taken the place. The Screaming Eagles had the time and opportunity to pick the town clean of prime souvenirs and take them home, forever associating themselves with the Nazi complex by their mementoes. Moreover, the 3rd Division, unlike the 101st, was not particularly adept at publicity. Major General O’Daniel and Colonel Heintges apparently thought that their arrival at Berchtesgaden would simply stand on its own merit, and they made little, if any, effort to promote their division’s accomplishment. So, gradually over time, the idea that the 101st had made it to Berchtesgaden first took on a life of its own until many accepted it as fact.

It is not, however, a fact: The 7th Infantry got to the Kehlstein Mountain first. Not only is this recorded in potentially biased sources such as Fedala to Berchtesgaden, the 7th Regiment’s World War II history, another history called The Third Infantry Division in World War II or the recollections of 7th Infantry veterans, but in other more neutral sources. Charles MacDonald in The Last Offensive, the Army’s official history of the final campaign in Europe, wrote of the race to Berchtesgaden that ‘motorized troops of the 3rd Division got there first, in the late afternoon of 4 May.’ General Eisenhower in his wartime memoir noted, ‘on May 4 the 3rd Division…captured Berchtesgaden.’ Even the 101st Airborne credits the 7th Infantry with getting to Berchtesgaden. Major General Maxwell Taylor, commander of the 101st, admitted in his postwar memoir, ‘3d Division units got into Berchtesgaden ahead of us on the afternoon of May 4.’

The history of the 101st Airborne Division in World War II, Rendezvous With Destiny, also records the true course of events. After chronicling how, on May 4, General O’Daniel sealed off the Saalach bridges to ensure that his units would win the race, the authors state: ‘At 1558 that day a motorized column [of the 3rd Division] entered Berchtesgaden; and that evening the 7th Infantry Regiment of the 3rd Division entered. When General O’Daniel received the message of his regiment’s entrance, he lifted his ban, allowed the 101st to come over his road, and Colonel Strayer [commander of 2nd Battalion, 506th] followed the 7th Regiment’s route.’ The authors of Rendezvous With Destiny estimate that Strayer’s soldiers reached Berchtesgaden sometime between 0900 and 1000 on May 5, a full 17 hours after the first Cottonbalers got there.

In spite of these indisputable facts, the myth still persists even today that troopers from the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, got to Berchtesgaden first. This is largely because of an honest mistake made by historian Stephen Ambrose in his otherwise excellent book Band of Brothers, which chronicled the experiences of one airborne unit — Easy Company of the 506th — in the war. Ambrose wrote of Berchtesgaden: ‘Everybody wanted to get there — French advancing side by side with the 101st, British coming up from Italy, German leaders who wanted to get their possessions, and every American in Europe. Easy Company got there first.’ In his research for the book, Ambrose heard the accounts of many Easy Company vets who honestly thought that they had won the race, and he never corroborated them with official, or even outside, sources. Inexplicably, Ambrose never even checked Rendezvous With Destiny, a source that would have alerted him to the fact that the 7th Infantry had reached Berchtesgaden on the afternoon of May 4. Indeed Ambrose wrote in Band of Brothers that Easy Company made it to Berchtesgaden on the morning of May 5. In so doing, he betrayed his ignorance of the facts of the race to Berchtesgaden and unwittingly (not to mention ironically) made the case that Easy Company had not gotten to Berchtesgaden first.

The smash success of Band of Brothers led Home Box Office to turn the book into a miniseries, in which the paratroopers were portrayed capturing Berchtesgaden. The continuation, on film, of this error led to an even greater proliferation of the myth, so much so that it shows up routinely in any discussion of Berchtesgaden. For instance, one reviewer of the Band of Brothers miniseries commented that the Eagle’s Nest was aptly named because the 101st Airborne Screaming Eagles had captured it.

This is quite unfortunate, perhaps even unjust. The Cottonbalers’ capture of Berchtesgaden is not open to debate. It is an incontrovertible fact and should be recognized as such. In emphasizing this point so vociferously, there is no intent to denigrate or dismiss the Band of Brothers book or miniseries. Both are excellent studies of the American combat soldier in World War II, but they propagated a myth that, in the interest of fairness and accuracy, needs to be redressed. Nor is there any intention of disparaging the considerable bravery and sacrifice of the 101st Airborne Division. The unit won great, and deserved, fame for itself, through the valor of its soldiers. Even so, the division should not receive plaudits for something it did not do. Plain and simple, those who achieved the prestigious conquest of Berchtesgaden should receive its laurels. Anything else is simply not fair to those who deserve the real credit — the Cottonbalers of the 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment.

No comments:

Post a Comment